After the pandemic (or during it) comes famine.

Food was already scarce before but the coronavirus pandemic has made shortages worse.

The world has never faced a hunger emergency like this, experts say. 135 million people have been already facing acute food shortages, but now with the pandemic, 130 million more could go hungry in 2020, doubling the number of people facing acute hunger to 265 million by the end of this year. 36 countries are at risk of famine.

7.8 billion people are hard to feed, especially when the soil is ruined by overuse, industrial farm practices, drought, and chemical contamination; especially when fish stocks are depleted, especially when ecosystems collapse, weather patterns change, and mass extinction leaves glaring gaps in natures tightly knit web.

Locust swarms are now ravaging Africa and the Middle East, affecting food production there. The United Nations has warned that an imminent second hatch of the insects could threaten the food security of 25 million people across the region. The outbreak is the worst seen in decades and comes on the heels of a year marked by extreme droughts and floods.

The fall armyworm is widely distributed in Eastern and Central North America and in South America. in 2016 it spread to Africa, where it caused significant damage to maize crops It has since infested 28 countries in Africa and was officially declared ineradicable.

In 2019 the fall armyworm was detected in China in the southwest province of Yunnan. Through 2019, the pest infested a total of 26 provinces. The armyworm is expected in 2020 to hit China’s northeastern wheat belt. A report issued by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs rates the situation as “very grave”. In February the pest was detected in Queensland, Australia.

Not to forget: We may be the last generation to catch food from the oceans, as around 85 percent of global fish stocks are over-exploited, depleted, fully exploited or in recovery from exploitation. Large areas of seabed in the Mediterranean and North Sea have been expunged of fish using increasingly efficient methods such as bottom trawling. As nothing is left to catch the heavily subsidized industrial fleets have turned to tropical seas and are cleaning up aquatic life there too. At the moment one-quarter of EU catch is made outside European waters, much of it in previously rich West African seas, All West African fisheries are now over-exploited and coastal fisheries have declined 50 percent in the past 30 years,

Supply chain disruption

Few images conjure the 1930s Depression better than people standing in long soup lines while farmers dump harvested food they can’t sell.

The coronavirus pandemic has shaken global food supply and could bring about a food crisis if governments fail to manage the challenge well, the heads of three global agencies — the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, the WHO (World Health Organization) and the WTO (World Trade Organization) have warned.

Amid disruptions in global production chains, countries are under pressure to seek “nativist” solutions and prioritize their own food security, with some banning exports of foods and others scrambling to stockpile as much as they can or produce locally what they used to import.

Food-exporting countries have begun to limit the free flow of food and goods. Kazakhstan, for instance, has suspended exports of several cereal products, as well as oilseeds and vegetables.

Russia, the worlds biggest wheat exporter, has instituted seven-million-ton caps on exports of essential crops as wheat, rye, barley, and corn. Members of the Eurasian Economic Union are excluded from the restrictions. The quotas are effective until June 30 and have been already fully exhausted.

Vietnam, the world’s third-largest exporter of rice, said it planned to stockpile the grain. Myanmar also restricted rice exports. Thailand banned shipments of chicken eggs to foreign nations after a domestic supply shortage.

ASEAN (the Association of Southeast Asian Nations) stepped in and called a (virtual) meeting where the members vowed not to restrict food exports. Vietnam and Myanmar lifted rice restrictions for May while Malaysia and Singapore struck a deal to fix a bottleneck at their border which had caused unsold melons to spoil.

Yet, this is not only a matter of national politics, it is a matter of a meticulously organized “just in time” flow of commodities between even the most distant regions of the world.

As sailors and dockers are infected, container ships are anchored, ports shut down, and borders closed, the entire global logistics chain for food has been disrupted for months, which has triggered a shortfall in food supplies in Asian, African, and Latin American nations.

Grain prices have risen sharply as many countries are already suffering from drought, and now imports have been impeded by the pandemic. Consumers’ panic buying over fears of long-term logistics disruptions has exacerbated the situation, with supermarkets in many countries facing difficulty putting food on the shelves.

Supply chain disruption in China

There is a Chinese idiom, “food is the god of the people.” With Sars-CoV-2 slowing down the production and movement of foodstuffs, the memory of the great famine of 1959-1961 lingers.

Even as China gets the outbreak under control, the country’s farmers are still struggling to plant crops and to feed their livestock, as their supply of fertilizer or high-demand imports such as soybeans has been disrupted. These farmers have already suffered huge financial losses as their produce has not been transported to markets for sale in more than two months.

The coronavirus is making it harder to grow food not only in China but also around the world, as lockdowns and travel restrictions cause labour shortages in the farming sector. Logistics disruptions have broken supply chains and severely obstructed the flow of food to China, the world’s largest food consumer and importer.

China, the world’s top hog producer, has been battling an outbreak of African Swine Fever since last year. The resulting supply disruption amid efforts to contain Sars-CoV-2 caused food prices to jump 21.4 per cent in February, largely driven by a 135.2 percent hike in pork prices (which was the biggest increase on record). Farmers were forced to slaughter millions of pigs and the outbreak reduced the nation’s pig herd by half, leaving many farmers penniless.

China is vulnerable to disruptions in the fragile global food-supply chain as it depends heavily on imports for some crops. With 9.5 percent of the world’s arable land and only 7 percent of freshwater resources, China successfully feeds 22 percent of the world’s population. It has achieved its strategic goal of becoming self-reliant in terms of its grain supply, with 95 percent of wheat, rice, and corn produced at home. China’s total grain output increased 74 percent from 354 million tonnes in 1982 to 618 million tonnes in 2017, surpassing the growth of its population by about 34 percent.

But China still relies on international markets for about 80 per cent of its consumed soybeans and agricultural staples such as milk and sugar.

Today’s Chinese want to eat more like their affluent counterparts in the developed world. For instance, China’s consumption of meat jumped from 7 million tons in 1975 to 75 million tons in 2017; the country now consumes yearly 50 kg of meat per capita. The rising meat consumption also explains why China’s soybean imports (commonly used for animal feed ) have increased exponentially, from 300,000 tons in 1995 to 95 million tons in 2017.

Supply chain disruption in USA

The USDA (US Department of Agriculture) announced plans to purchase excess food from farmers to distribute to food banks and charities to meet the growing need and prevent food waste. Yet, millions of pounds of food are still being destroyed or left to rot in the fields and the New York Mission Society estimates that one-third of food banks across the country have already closed due to a lack of funding and supplies. The remaining food banks and soup kitchens scramble to meet a massive surge in demand.

The nation’s largest dairy cooperative, Dairy Farmers of America, estimates that farmers are dumping as many as 3.7 million gallons of milk each day. The New York Times reported that a single chicken processor is smashing 750,000 eggs a week.

Poultry and livestock farmers have begun culling their animals. They are sending all their herds to early slaughter because the catering market is dead and so, at the most basic level, nobody in the US is going out for steak and eggs or a nice bacon and egg breakfast in a diner. It takes time to rear cattle to ideal slaughter size and age (less time for pigs and poultry) and farmers are unlikely to start rearing until they are certain that there will be a market for the meat when the time comes, so there will be a gap of several months. Frozen meat will make up for some of the shortfall, but beef prices are likely to soar.

Imports will not be able to fill the gap. Brazil, the world’s number one shipper of chicken and beef, saw its first major closure with the halt of a poultry plant owned by JBS SA, the world’s biggest meat company. Key operations are also down in Canada, the latest being a British Columbia poultry plant.

The virus is spreading fast among meat-plant employees, as low-wage migrant workers live in cramped quarters and are in close proximity (elbow-to-elbow). These plants see thousands of people coming in and out every day — it is the opposite of social distancing.

The processing of hogs has fallen by a third and cattle by 12 percent compared to the usual output. Hogs are raised in cramped, temperature-controlled facilities and fed grain to hasten fattening. If they are not slaughtered in time, they will break their legs because of their heavy weight.

Farmers may need to start euthanizing 60,000 to 70,000 pigs per day as slaughterhouses shutter due to rising coronavirus infections among the meatpacking industry workforce. But burning, burying, or composting up to 70,000 hog carcasses a day — or even grinding them into dust — could have serious consequences for air and drinking water.

At least 22 major meat facilities have temporarily halted in the space of a few weeks, including slaughterhouses owned by the nation’s biggest poultry, pork, and beef producers, such as Smithfield Foods, Tyson Foods, Cargill, and JBS USA.

US President Donald Trump ordered meat processing plants to stay open to protect the nation’s food supply after one of the country’s largest pork processing facilities, owned by Smithfield Foods, shut down when 230 workers contracted Sars-CoV-2. An estimated 3,300 US meatpacking workers have been diagnosed with coronavirus and 20 have died.

Hog farmers nationwide will lose an estimated 5 billion US$ for the rest of the year due to pandemic disruptions, according to the industry group National Pork Producers Council.

Poultry is down 10 percent as the biggest poultry plants have closed, and experts are warning that domestic shortages are just weeks away. Roughly 90 percent of all broiler chickens are produced under contract with just three large corporations, and 57 percent of hogs are owned and slaughtered by just four companies. Farmers are forced to follow the instructions of their contractors (one of these giant corporations) or risk retribution or even financial ruin.

Two factors are changing and impeding the way of food distribution. a) The pandemic caused a shift to eating nearly all meals at home. Before, a significant amount of daily food consumption was via restaurants and institutions, particularly school and university cafeterias. Those kitchens bought in bulk and used different wholesalers than grocery stores and supermarkets, who deal almost entirely in smaller package sizes, as well as more prepared items (like frozen meals and dishes, canned and packaged soups). So there’s a big mismatch between supply and demand. b) Sars-CoV-2 induced closures of meat processing plants and a shortage of farm workers have hurt both farmers and consumers.

Prices are surging. US wholesale beef touched a record this week, and wholesale pork soared 29 percent, the biggest weekly gain since 2012. As demand escalates, the price of non-perishable staples such as peanut butter, eggs, canned vegetables, beans, pasta, rice, and jam is soaring, while supplies are running low with four- to eight-week delays and bottlenecks reported across the supply chain. There are numerous cases of price gouging. Lawsuits in California and Texas for instance contend that egg producers or supermarkets charged excessive, illegal prices for eggs.

The Coronavirus Food Assistance Program, a 19 billion US$ plan purportedly aimed at providing relief to farmers and making mass purchases of dairy, meat, and agricultural produce to get that food to the people in need, is criticized as inadequate.

Food scarcity

From Lebanon to Honduras to South Africa to India, protests and looting have broken out amid frustrations with lockdowns and worries about hunger. With classes shut down, over 368 million children have lost the meals and snacks they normally receive in school.

In India, thousands of workers are lining up twice a day for bread and fried vegetables to keep hunger at bay. In the Kibera slum in Nairobi, Kenya’s capital, people desperate to eat set off a stampede during a recent giveaway of flour and cooking oil, leaving scores injured and two people dead. Across Colombia, poor households are hanging red clothing and flags from their windows and balconies as a sign that they are hungry.

There is concern that food shortages will lead to social discord. In Colombia, residents of the coastal state of La Guajira have begun blocking roads to call attention to their need for food and in South Africa, rioters have broken into neighborhood food kiosks and faced off with the police.

Even before the pandemic it was estimated that more than five million Afghan children needed some form of humanitarian support. Latest UN surveys indicate that about two million children aged under five face extreme hunger. The NGO Save the Children reports that more than seven million children in Afghanistan are at risk of hunger as food prices soar due to the pandemic.

In the UK, almost a fifth of households with children have been unable to obtain enough food in the past five weeks, according to the London-based NGO the Food Foundation. 30 percent of single parents and 46 percent of parents with a disabled child experiencing problems in receiving food.

Poorer families used to rely on free breakfast clubs and school lunches but have now lost access to them as schools remain closed. The situation has been exacerbated by many losing jobs and income due to the lockdown.

The UK’s biggest food bank network, the Trussell Trust, previously said that it saw its busiest period ever after the lockdown was imposed at the end of March, when the amount of food it gave out almost doubled. Another charity, IFAN (the Independent Food Aid Network), reported that the demand for emergency food has gone up by nearly 60 percent.

Hunger was already before the pandemic a widespread and persistent problem for US-inhabitants. A Department of Agriculture report released last year found that 37 million people in the United States were affected by hunger issues at some point in 2018. Households with children are also more likely to experience food insecurity and these households rely heavily on food banks and similar hunger-relief institutions. In 2019, an estimated 40 million Americans received free meals or groceries through a network of 200 food banks and 60,000 pantries, schools, soup kitchens, and shelters. The majority of these meals were typically given to the working poor, elderly, and disabled.

Queues up to 10 kilometers long have become common at pop-up collection points in San Antonio, Las Vegas, Cleveland, and other cities, where thousands of recently furloughed and unemployed people wait hours for grocery boxes. In San Antonio 10,000 people showed up in their cars to a food distribution drive-through service. The center usually saw 400 people before the pandemic occurred. Much of the semi-truck loads of food were handed out to newly laid-off hospitality staff whose last paycheck had been exhausted.

In Louisiana, which has been another major hotspot of the pandemic’s spread, at least one in three people are at risk of hunger,

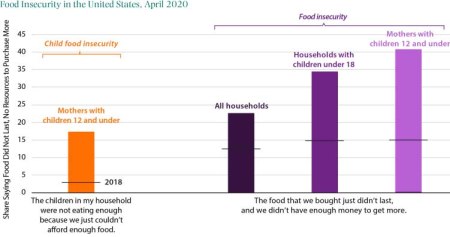

Results from two recent surveys show that by the end of April 2020, more than 20 percent of all US households and over 40 percent of mothers with children under the age of 13 were experiencing food insecurity. These figures are between two and five times greater than they were in 2018, when food insecurity data was last collected.

Feeding America, the largest food bank operator in the USA, warned in a report that the coronavirus crisis could lead to an all-time high in child hunger as millions of families struggle to cope with the devastating economic fallout. The report found that “the number of food insecure children could escalate to 18 million because of the coronavirus pandemic”.

Lauren Bauer, a fellow in Economic Studies at the Brookings Institution, writes in a blog post: “Looking over time, particularly to the relatively small increase in child food insecurity during the Great Recession, it is clear that young children are experiencing food insecurity to an extent unprecedented in modern times.”

Food industry

Social distancing is a big problem for production and further processing of food. At the simplest level, if you space staff in the fields or on a conveyor belt two meters apart instead of one, you effectively halve your production rate. Adding extra shifts or extra lines will increase costs and mean higher food prices.

A significant factor in meat production has been the development of CAFOs (Confined Animal Feeding Operations). These CAFOs are large facilities with temperature-controlled environments in which pigs can be fattened quicker and production can be concentrated spatially.

CAFOs have destroyed independent producers by securing grain subsidies from the state for decades, making it possible for CAFOs to out-compete and conquer the market.

These policies resulted in higher profits for corporations but can hardly be considered a positive development in production. A study published by the Union of Concerned Scientists in 2008 details how CAFOs were only made economically viable through government intervention. It also determined that alternative methods of production would be just as productive without the additional financial and environmental costs. The study estimates that CAFOs add an additional $5 billion in costs through externalities.

CAFOs are also notorious for causing environmental damage. Improper animal waste disposal by multiple large operations has been found to have contaminated the soil and ground water of neighboring communities.

The meat industry, just like any other industries, has become increasingly reliant upon the “just-in-time” mechanics of production. This means that animals are moved through facilities at a pace that requires the least amount of storage capacity in order to lower costs.

Industrial agriculture

Agricultural activity is a key driver of overgrazing, soil exhaustion, desertification, and ecosystem destruction (forests, wetlands, waterways, and oceans). Its expansion is one of the main causes of biodiversity collapse. Moreover, agriculture (together with forestry) accounts for 23 percent of human-induced greenhouse-gas emissions contributing to climate change.

Modern day highly specialized farming depends on the smooth movement of seasonal workers for the short harvest period of the monoculture farms and plantations. Without seasonal migrant workers, vegetables and fruits will rot, fields, plantations, orchards, and vineyards will left unattended. Without migrant workers meat farms and slaughterhouses will have to close.

With the sudden restrictions on border crossings (many seasonal workers come from eastern Europe, North Africa, and Latin America) and increasing challenges to the global shipping industry, suddenly the vulnerability of long, intricate, and tightly-tuned supply chains of the industrial food system become apparent.

Quarantine controls imposed by various governments prevent seasonal workers from getting to farms where their labor is needed. As spring starts in America and Europe, farms are rushing to find enough workers to plant and harvest crops as border closures prevent the usual flow of foreign laborers. France has already called its own citizens to help offset an estimated shortfall of 200,000 workers.

Border closures, travel restrictions, shipping delays because of outbreaks among sailors, lockdowns, and quarantine measures all make food distribution across continents more difficult. As a result food will become scarce and expensive, but a global food crisis looms anyway because of natural disasters (droughts, floods, storms) and pests (locusts, fall army worms, rice blast, wheat rust, brown streak, potato blight, etc.).

Also, as already mentioned, if social distancing is practiced, yields go down unless you add many more staff. That, of course increases costs.

Even in rich countries food disruptions will become more frequent.

The disruptions in food processing are happening at a time when global meat supplies were already tight.

Feeding animals becomes more expensive as crude oil prices are down and subsequently the ethanol market is dead. Nobody’s making ethanol, which means a shortage of animal feed because usually after fermentation the mash would be dried, pelletized, and fed to animals.

One example out of many:

Turkey’s long-running problem of agricultural shortages and food inflation could worsen under the impact of the coronavirus pandemic, as the government has relied on imports to fill the gaps instead of encouraging domestic production.

Turkey turned into an importer of livestock and raw materials for vegetable and animal production, frustrating its own farmers. The main products for which Turkey relies on imports to cover domestic demand include wheat, barley, corn, cotton, soybeans, sunflower seeds, paddy, haricot, red lentils, and chickpeas.

Price increases in agricultural inputs, many of them imports, had alarmed Turkish producers even before the pandemic. In February, for instance, seed prices were up 19 percent on a year-on-year basis, followed by increases of 18 percent in fertilizer prices, 12 percent in fodder, and 8 percent in pesticides.

Local food, slow food, and subsistence

The convenience trap has trapped us all. Instead of planting, irrigating, weeding, pest control, pruning, harvesting, and processing we now just go shopping and take the neatly in plastic film packed items from the shelves.

This is easy, but despite the convenience there still were people who for many years abhorred the industrial food system and tried to “live from the land.” There were families, communes, communities, and activist groups who tried to become independent by growing their own food in subsistent gardens or farms and using both traditional and modern methods to store them for winter. Until now they were ridiculed, they were laughed at.

Ideally communities should learn to produce locally all these foods they before the pandemic had carelessly imported. This obviously cannot be achieved overnight, even if decision-makers are prepared to go ahead with measures to do so. Political directives are important still, as local farmers and co-ops need to have confidence that they are being protected, encouraged, and supported,

Ideally one should grow the food by oneself, to make sure that it is grown without chemicals and not contaminated by pesticides or substances like BPA, leaking from packing materials. This will be arduous, laborious work for sure and it makes elementary lifestyle changes necessary.

Not everybody will be able to give up a career, move to the countryside, buy or lease some land, or join a co-op. Specialization will continue, though it could be healthy and even increase productivity and creativity if people spend only half of the day as telecommuters in front of a screen and the other half in the garden or field.

Some people will miss the noise and distractions of urban life. They will never become gardeners and farmers but they can at leasts contribute with piecemeal changes of routines and practises.

People are now shopping once a week, like they did 10 or 20 years ago, rather than two, three, or four times a week as it happened before the crisis. The priority is to keep staff and shoppers safe. Most of the customers have adapted to the changes in stores, wearing masks and maintaining social distance. The challenge will be keeping the discipline in smaller stores when people return to work and are in a hurry.

Online orders will become an alternative to traditional shopping. This means of course that Jeff Bezos (Amazon) and Pierre Omidyar (eBay) will become even wealthier. Searching for alternative online sources may pay off. If one lives in a rural area one definitely should check out nearby organic farms, gardeners, and bakeries.

A well designed and maintained delivery system could mean some fuel savings.

Tesco in the UK has achieved an increase in online capacity of 103 percent in the space of a few weeks, growth which would normally take years to achieve. The other supermarkets have also ramped up delivery slots. Before the crisis, only about 7 percent of all groceries were bought online.

Vietnam has experimented with novel ideas, such as a “rice ATM (automatic teller machine),” a machine that dispenses free rice, and a “zero cost” grocery store, which lets the needy take five free items per person, such as noodles or bananas.

Former Vietnamese diplomat Ton Nu Thi Ninh said she hopes these ideas will continue after the crisis: “The coronavirus global pandemic is laying bare much of what is wrong with our societies,”Ninh, now president of the Ho Chi Minh City Peace and Development Foundation, continued: “At the same time it is activating inherent goodness in many of us, stimulating relief and philanthropic initiatives.”

As a concluding point: To truly be resilient, the food system must shift to one that relies on small and medium producers and local independent, responsible operations.

The California Center for Cooperative Development, which is based in Davis, tries since years to sell the idea of co-operatives and the program progressively is getting traction.

Founded in 2011, FEED Sonoma is a food-hub community of 80 local farms, supporting ecologically sustainable farming and ranching practices. FEED Sonoma is also California’s first farmer- and worker-owned fresh produce cooperative.

Thousands of families affected by the lockdown and eager for fresh healthy food have signed up online for boxes filled with romaine lettuce, radishes, kale, savory spinach, white turnips, spearmint, Valencia oranges, and other vegetables or fruits.

Members of the cooperative, all wearing masks and gloves, fill boxes twice a week at a warehouse near Penngrove. The customers then pick up the boxes at a dozen distribution points, from Healdsburg to the town of Sonoma and all the way to Oakland. With the arrival of summer, there will be strawberries and much more in every box. Weekly and bi-weekly subscriptions are offered.

During the last few weeks, sales have jumped from 90 boxes to 450 and then to 1800. The goal is 4,000. Contact: feedbin@feedsonoma.com

Also from California: A poem from Cathy Thwing(https://cathytea.wordpress.com)

Whose hands touched this apple that I wash under filtered water?

My hands, scrubbing its rose-freckled skin.

The delivery shopper’s hands, picking it from the bin,

placing it in a bag, leaving it by our gate.

The checker’s hands, assessing its weight.

The produce stocker’s hands, setting it stem-side up.

My hands, scrubbing its rose-freckled skin.

The delivery shopper’s hands, picking it from the bin,

placing it in a bag, leaving it by our gate.

The checker’s hands, assessing its weight.

The produce stocker’s hands, setting it stem-side up.

Another man, with a label-gun, doing the follow-up.

A customer’s sticky hands, the hands of her kid,

think of the germs that might be hid

from view. Invisible. My hands scrub the apple

under filtered water. This is the fact with which I grapple:

the coronavirus lives 72 hours on a surface.

A customer’s sticky hands, the hands of her kid,

think of the germs that might be hid

from view. Invisible. My hands scrub the apple

under filtered water. This is the fact with which I grapple:

the coronavirus lives 72 hours on a surface.

Still, I am grateful for the service

of the laborer who picked

this fruit as the work clock ticked

and the hands of the orchardist

who planted the tree in the mist

of an early spring morning in Washington,

or J.H. Kidd, horticulturalist, whose discovery, once begun,

led to this apple, in my hand, under running water, a red-freckled Gala.

of the laborer who picked

this fruit as the work clock ticked

and the hands of the orchardist

who planted the tree in the mist

of an early spring morning in Washington,

or J.H. Kidd, horticulturalist, whose discovery, once begun,

led to this apple, in my hand, under running water, a red-freckled Gala.

I try to soothe my amygdala.

Whose hands? An apple a day,

now that my hair is gray,

adds to 21,900 pippins, red delicious, Macintosh

Granny Smith, ambrosia–oh my gosh

if each apple were touched by 50 hands

that’s thousands and thousands

and all the germs and the fingerprints

and all the skin oil and imprints

of feelings. Including the love that my mom and dad

felt for me. Remembering childhood apples, I don’t exactly feel sad.

Whose hands? An apple a day,

now that my hair is gray,

adds to 21,900 pippins, red delicious, Macintosh

Granny Smith, ambrosia–oh my gosh

if each apple were touched by 50 hands

that’s thousands and thousands

and all the germs and the fingerprints

and all the skin oil and imprints

of feelings. Including the love that my mom and dad

felt for me. Remembering childhood apples, I don’t exactly feel sad.

It’s wistful, yeah, but it’s more the continuity.

I look at this shiny wet apple with ambiguity.

So many hands to bring it to me.

All those feelings, soon to be inside me.

Whose hands touched this apple?

I look at this shiny wet apple with ambiguity.

So many hands to bring it to me.

All those feelings, soon to be inside me.

Whose hands touched this apple?

Keine Kommentare:

Kommentar veröffentlichen