Built in 1969, the chemical plant in Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh state, was seen as a symbol of a new industrialized India, generating thousands of jobs for the local population and manufacturing cheap pesticides (like the insecticide Sevin) for millions of farmers. The factory was owned by the US multinational UCC (Union Carbide Corporation).

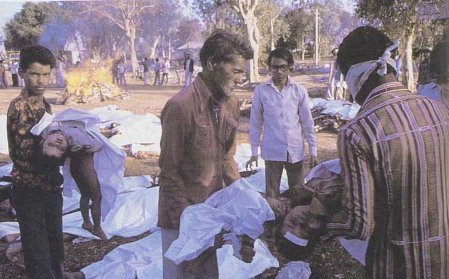

Then, on the night of December 2, 1984, exactly 30 years ago, the plant leaked 40 tons of methyl isocyanate gas into the air, killing thousands of largely poor Indians in the surrounding villages. The cause of the catastrophic accident remains unclear even today and nobody has been charged.

The government recorded 5,295 immediate deaths, while up to 26,000 people died in the aftermath and the following years.

Another 100,000 people who were exposed to the gas continue to suffer today with sicknesses such as cancer, blindness, respiratory problems, immune and neurological disorders. Children born to survivors have mental or physical disabilities. Children are born with twisted limbs, brain damage, musculoskeletal disorders. These are not rare conditions, every fourth or fifth family has a disabled child. There is also a very high prevalence of anemia, delayed menarches in girls and painful skin conditions.

The toxic legacy of this factory lives on, as at least 500 tons of hazardous waste remain buried in 21 pits within the 68-acre site or hidden in the wasteland outside, slowly poisoning the drinking water of some 60,000 people and affecting their health.

Water samples taken from around the site contained chlorinated benzene compounds and organochlorine pesticides 561 times the national standard; the government was forced to recognize the water contamination in 2012 when the Supreme Court ordered that clean drinking water be supplied to 22 communities near the factory.

Activists want the toxic waste removed and disposed of away from the area, and they accuse Indian authorities, who now own the site, of negligence and inaction, failing either to clear up the waste themselves or forcing Union Carbide to take responsibility.

While those directly affected receive free medical care, authorities have failed to support those sick from drinking the contaminated water and a second generation of children born with birth defects.

Dow Chemical, who took over Union Carbide in 2001, denies responsibility, saying Union Carbide spent two million US$ on remediating the site, adding that Indian authorities at the time approved, monitored, and directed every step of the clean-up work.

Union Carbide was sued by the Indian government after the disaster and agreed 1989 to pay 470 million US$ in an out-of-court settlement. The company says the Indian government then took control of the site in 1998, assuming all accountability, including clean-up activities.

“While Union Carbide continues to have the utmost respect and sympathy for the victims, we find that many of the issues being discussed today have already been resolved and responsibilities assigned for those that remain,” Tomm F. Sprick, Director of the Union Carbide Information Center, told the press per email.

An Indian High Court ruling had ordered the state Madhya Pradesh in 2004 to incinerate 350 tons of toxic waste after tests at Pithampur in Madhya Pradesh’s Dhar district. But the order was not fulfilled after stiff opposition by NGOs which claimed that the waste disposal at the incinerator would harm Pithampur’s people and its environment. Subsequent attempts to dispose the waste at Gujarat’s Ankleshwar incinerator and at the DRDO (Defense Research Development Organization) facility near Nagpur were evenly foiled by environmental NGO’s.

In 2012 the waste removal was discussed with the German government agency GIZ (German Society for International Cooperation). The GIZ subsidiary International Services was ready to transport 350 tons of toxic waste to Germany for disposal at an incinerator in Hamburg. This plan failed too because of fierce protests by environmental groups in several European countries

In a major blow to the victims of the Bhopal tragedy, a US court on July 30 2014 ruled that UCC (Union Carbide Corporation) cannot be sued for the ongoing contamination from the chemical plant and that the state Madhya Pradesh doesn’t need to cooperate in the clean-up of the site.

US District Judge John Kennan said in his 45-page ruling that: “The only relief plaintiffs seek against Madhya Pradesh is an injunction directing them to cooperate in clean-up of the site ordered by this Court against UCC.”

“Because I conclude that there is no basis to hold UCC liable for Plaintiffs’ damage, there will be no court-ordered cleanup in this action, and thus, no basis for enjoining Madhya Pradesh. It is therefore appropriate to enter judgment in favor of the state (in) the amended complaint.”

Chemical plants like The UCC facility in Bhopal are located in many places all over the world and there were various accidents before and after Bhopal. A few examples:

In 1948 a chemical tank wagon explosion killed 207 at the BASF plant in Ludwigshafen, Germany.

In 1971 an explosion at a Thiokol chemical plant killed 29 in Georgia, USA .

In 1974 an explosion at a chemical plant near the village of Flixborough, Britain caused 28 fatalities.

In 1984 an Union Oil refinery explosion killed 19 people in Romeoville, Illinois, USA.

In 1988 a Shell Oil refinery explosion killed 7 workers in Norco, Louisiana, USA.

In 1989 an explosion and fire at the Phillips plant killed 23 in Pasadena, Texas, USA.

In 1990 an explosion and fire at the Arco Chemical Company complex killed 17 in Channelview, Texas, USA.

In 2001 an explosion at the AZF fertilizer factory killed 29 and injured 2,500 in Toulouse, France.

In 2005 an explosion at the BP refinery killed 15 and injured 100 in Texas City, Texas. USA.

In 2013 a fertilizer plant explosion in West, Texas, USA killed at least 14 and injured 160.

Chemical production not only endangers the immediate neighbors of factories, it also causes toxic waste and contamination of air, water, and soil.

A study from the Blacksmith Institute and Green Cross in November 2013 concluded, that at least 200 million people around the world are at risk of exposure to toxic waste. The study surveyed 3,000 sites in over 49 countries and identified the Agbobloshie dumping yard in Ghana’s capital Accra as the place which poses the greatest threat to human life.

Another study by Blacksmith analyzed water and soil samples at 373 waste sites in India, Indonesia, and Pakistan. The samples showed that more than 8.6 million people living near the sites in 2010 were being exposed to a soup of toxic substances, including jead, chromium, phosphates, different kinds of organic chemicals (POPs), pesticides, etc.

Fortunately for Western consumers most industrial production has been outsourced to countries where it only affects unimportant brown or yellow people.

In China’s south-central Hunan province, non-ferrous metal mines generate almost 50 million tons of waste a year. Of the more than 160 types of minerals that have been discovered in the world, 140 — including tungsten, antimony, bismuth, zinc, lead, and tin — are found there. Soil samples have shown 1,500 times the permitted levels of heavy metals.

Don’t deride China, a recent study of Vancouver community gardens and agricultural soils near roads has found elevated levels of lead and other metals high above Canadian standards for human health.

The poisonous substances which are produced in chemical plants or mines all become ingredients of consumer goods and building materials or get used in industrial agriculture.

Fields, plantations, and orchards are doused with neonicotinoids, 2,4-D, glyphosate, atrazine, and other pesticides. These poisons decimate wildlife (bee colony collapse) and contaminate all industrial produced food.

Food is also contaminated by packaging materials. Most plastic products, from baby bottles to meat trays to takeout containers to food wraps release chemicals which the human body misinterprets as hormones (endocrine disrupters). It is not only the widely discussed bisphenol A, but also polystyrene resin, Tritan (containing TPP), and additives like dyes and antioxidants, which leak into the food.

These chemicals can cause asthma, cancer, infertility, heart disease, ADHD (attention-deficit / hyperactivity disorder), diabetes, etc.

Furniture and textiles contain flame-retardants like chlorinated Tris and TCEP. Glycol ethers are solvents commonly used in paints and cleaners, they can cause anemia, intoxication, and irritation of the eyes and nose. Triclosan, a chemical ingredient of cosmetics, soaps, detergents, shampoos, and toothpaste has been found to trigger liver cancer in laboratory mice.

One should open the windows and ventilate the rooms frequently to avoid an accumulation of toxic fumes from the various synthetic materials in the home. One should close the windows to avoid smog, ground-level ozone, exhaust fumes, and soot from heating furnaces.

One better stops breathing and eating altogether,

One better stops drinking, because potable water contamination is widespread. 90 percent of drinking water in Chinas cities is polluted.

Pesticides, fertilizers, micro-plastics (from personal care products), heavy metals, pharmaceuticals, chromium-6, and other dangerous substances contaminate all waterways and many wells, some of them cannot be removed by water treatment plants.

So we need to buy bottled water, contaminated with chemicals that are leaking from the plastic bottle.

Or we stop buying products with synthetic materials, using natural materials like fibers (hemp, cotton, wool, silk), wood, stone, clay, ceramic, bone, etc.

No, this is impossible, we cannot go back to the Stone Age, we cannot dismiss technological progress with all the amenities it includes, the doubters will say.

Renouncing the ubiquitous plastics is indeed nearly impossible. How did people live without them only a bit more than a hundred years ago? Parkesine was invented in 1862, celluloid in 1868, bakelite in 1897.

Some people lived quite comfortable in these plastic-less times, many others lived in misery — just as it is now. The misery was of a different kind of course.

Maybe we don’t have to return to the pre-plastic age, maybe we can make a compromise. What about scaling back the acquisition of new stuff, using less and using it for a longer time?

Is it too much asked?

Keine Kommentare:

Kommentar veröffentlichen